"Now then, Dmitri, you know how we've always talked about the possibility of something going wrong with the Bomb..."

- President Merkin Muffley, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

This Brasileirão's season has brought up many discussions over the influence of possession in winning's probability. Many posts circulating afirm that: teams that have more possession usually win. Many posts like here, here, and here (Note: all posts are in portuguese). According to Guilherme Marçal, who writes for the column "Espião Estatístico" of Globoesporte.com, only 24.3% of games the team with less possession ended winner (see here).

These conclusions are quite intriguing, however, teams with less possession taking advantages in Brasileirão is not something new. See the column “Não queremos a bola”, by Mauro Cézar Pereira, at ESPN portal. Data brought by Mauro shows us that this has happened since 2013.

However, Renato Rodrigues, from DataESPN, in a recent post (read here), brings a crucial point into this discussion: what is possession? What is its definition? How are the minutes counted, when the ball is not in play? These numbers of possession do take into consideration moments that the ball is still, waiting for a foul, penalti or corner to be taken? The problem with "possession" statistics is that we do not know exactly how it is measured. When we watch a match by TV, at no moment you hear a pundit defining "possession"; the numbers are simples exposed on the screen as its definition were as clear as shots in goal, fouls or innacurate pass. But that is not the case.

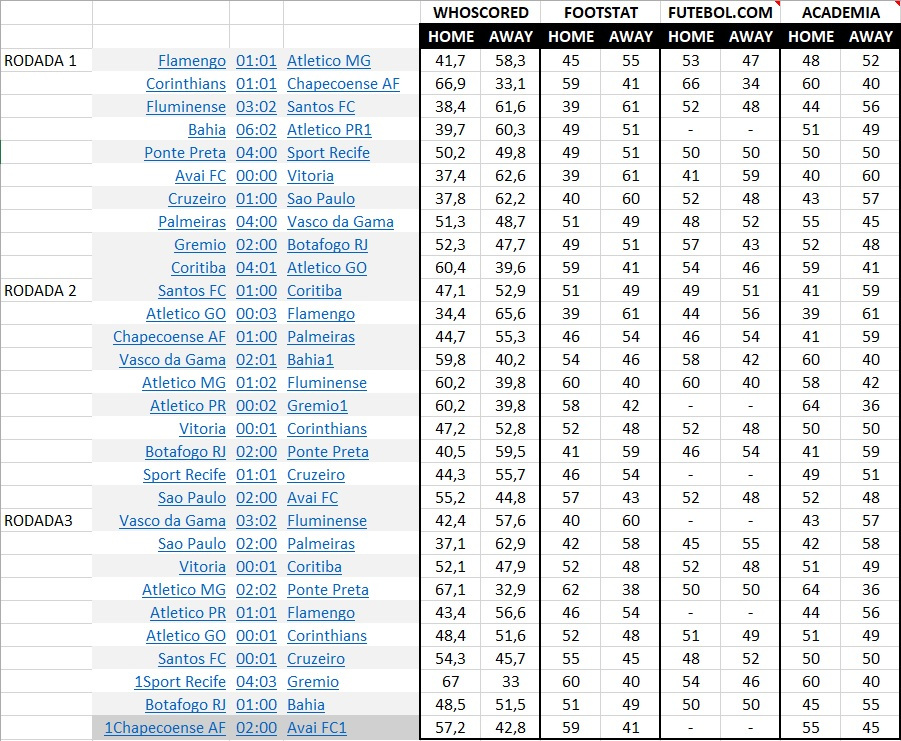

To show the importance of defining how the possession is measured, I searched for possession data for the three first rounds of 2017 Brasileirão, in four distinct sources: 1) whoscored.com, Footstats platform; betting sites; 3) futebol.com and 4) academiadasapostasbrasil.com. The results are in the table below. In most cases, the percentages of possession difer. Each website provide a different number. The differences vary from 1 to 17 percentage points! That's right, the difference in possession, for the same match, can get to 17%. The average difference is 7 percentual points in each match. Besides, only in 56.7% cases, all sites agreed which team ended the match with more possession! For example, Palmeiras 4x1 Vasco, for the first round of Brasileirão; whoscored.com, Footstat and Academia das Apostas agreed that Palmeiras had more possession (51.3%, 51% and 55%, respectively). But, futebol.com shows us Vasco with 52% of possession. There are many other examples, have a look at Table 1.

Values in percentage

All these websites provide possession statistics, but, in none of them the definition is clear of how it is calculated. Probably these websites have different definitions for possession, and that's why the numbers diverge in Table 1. Besides, these definitions are not clear, there is no explanations in their pages. We don't know what is behind those numbers. In a nutshell, possession is a black box.

If we want to understand better possession in football, first we need a clear definition of how it is measured. And then, we need to understand how to analyze it.

Having that in mind, I calculated possession for all Brasileirão matches, until round 25. I built the possession statistic with the following definition: only moments which the ball is in play and the game is not stopped are counted. Moments that teams are still preparing for a throw in, a corner, goal kick, or event when the doctors come into the pitch to check on a player, are not taking into account as possession for any club. Moments that the ball is moving, after a offside, are also not taken into account. Clearences are not taken into account either, until the player of any team touches the ball again.

Well, starting from this definition of possession, I checked the frequence of winnings of clubs with more possession. The result is that only 26% of matches, the winner is the club that ended the match with bigger possession. That is, my statistics of possession corroborate with the evidence suggested by all the posts above. At first sight, it seems that the numbers tell us that bigger possession is associated with less number of goals.

So it means that small ball possession is associated with bigger number of goals scored? Does it mean that brazilian clubs do not know what to do with the ball? How can we understand these data?

Well, to answer these questions, we first need to know how to analyze the stats. The first thing to do is distinguish were possession in concentrated: possession in the defensive half does not help the team to score. The second thing we should consider, and what I think is the most important - and the one I'm focusing in this post - is: the goal changes the game! A goal changes the game in many aspects; one of them is that teams that score, winning the game, tend to "hand" the ball to the opponent. Many times we watch a match that is even until one of the teams scores, and right after the match restarts, the club the is losing has more possession and pressures the other team. That is quite common. Why? Well, there are many tactical or psychological explanations for that, but the fact is that the goal changed the game. In the world of football analytics, this concept is called game state. It is not new, and is used quite a lot in analytics, see here.

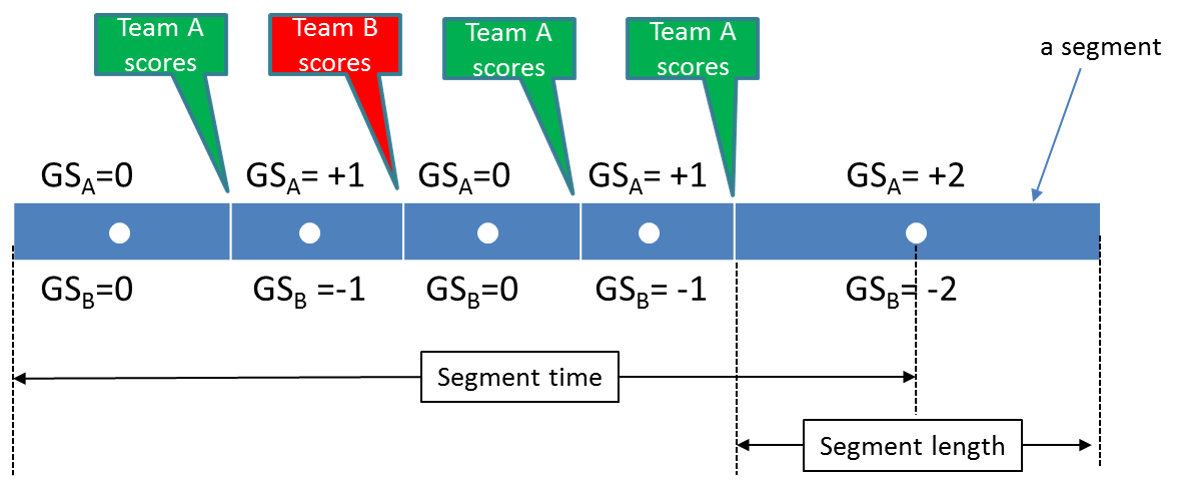

How is game state defined? The figure below explains how we defined that variable. Suppose the match is tied, team a 0x0 team B. So both are in the game state 0. At the moment team A scores, that is, team A 1x0 team B, team A goes to game state 1 and team B goes to game state -1. If after a few minutes team B scores, that is, team A 1x1 team B, the game state goes back to 0 for both. The game state is the goal difference that each team faces for every moment of the game. Figure 2 clarify how the game states are computed during a match.

GSa = team A's game state, e GSb = team B's game state.

The game state is important in assessing ball possession if clubs tend to "give in" possession as they move forward on the scoreboard. Therefore, if this is true, it is important to analyze ball possession in each time segment defined by game states (which is called segment length in Figure 2). Well, common sense tells us this is true, but is this true in the data? Yes. Table 2 shows the correlation between game state and possession of the ball for 4 competitions (Brazilian, English, Spanish and German) between 2013 and 2017. To arrive at these correlations, I calculated the game states of each game for championship. Each game was divided into game states according to the occurrence of goals. This was done for every game. From this, I calculated the possession of each team's ball during each game state, that is, possession of the ball during the segment length (see Figure 2). The possession of the ball was calculated according to the definition given above (only when the ball is on the field and the game is not stopped). With this database we can verify the linear relation between the possession of the ball and the game states of each game.

The correlations are negative for all league and years analyzed. That is, clubs that are winning are associated with less possession during that game state. The more goals ahead a team is (in number of goals), the BIGGER their game state is, and, at the same time, SMALLER their possession is. Therefore, data show that when a club is winning, he tends to "hand" the ball to opponent. That is true in Brazil, England, Spain and Germany, that is, the main leagues. The correlation coefficients are more negative for the brazilian league than for europeans, and that means that his "deliver" of possession to the opponent occurs more frequently in Brazil.

Flamengo 0x1 Grêmio, for the 13th round of Brasileirão, is a good example. Despite the winning of the gaúcho club, with a goal scored by Luan at 26 minutes of first half, Flamengo ended the match with 58% of possession. However, splitting the match by game states, we have that until Grêmio scored, at 26 minutes of first half, Grêmio had 52% of possession. They had a slightly superior possession until the goal was scored. Between Grêmio's goal and the end of the game, Flamengo had 62.1% (making the weighted average between the two game states go to the 58% described before). Therefore, if we look only to the possession at the end of the game, we would make the mistake of claiming that Gremio, even with a inferior possesion, scored a goal. In reality, Grêmio scored at a moment that they had more possession than Flamengo. After the goal, Grêmio "handed" the ball to Flamengo, that could not score (for Grêmio's luck/competence).

If the winning side ended the match with less possession, we can't claim that the concept of Pep Guardiola's play is wrong, or that the data are refuting the play concept of the catalan coach. What might be going on is that winning teams have more possession until the moment they score a goal, and after that, they "hand" the ball to opponent and defend more. That makes that, at the end of the match, the winning side presents less possession, but they may have had more while the match was tied. If that is the case, it get's clear that more possession is positively associated with scoaring a goal; however, if we just look at possession at the end of the match, we won't be able to see that. Therefore, if we don't consider conditional ball possession to the game state, we can conclude, wrongly, that having less possession is more effective to score goals; when in reality, it is the exact opposite.

For this Brasileirão's season (until round 25), we have that in 58% of the times a team untied the match, they had a bigger possession until the moment of the goal. That is, in most cases that a team was ahead in the scoreboard, they had more possession until the moment that goal was scored. The same takes place in all european leagues, although, in Europe this frequency is much bigger than in Brazil (in the english 16/17, for example, around 60% of the times that a team untied the match, they had more possession).

Thus, bigger ball possession is associated with more goals scored. So, what we have is not the effect described by Figure 1, but the effects described by the Figure 3, right below.

More possession is associated with more goals, while more goals are associated with less possession.

There are two effects: 1) more possession increases the chances of scoring a goal (positive effect), but, after scoring; 2) the team decreases theur possession (negative effect). The simple correlation between possession at the end of a match and number of goals shows us a net effect that is negative. But what is interesting is to evaluate the effect of possession in goal socring (we want to measure the effect of the right arrow in Figure 3). When we control for game state, we see that, in reality, bigger possession is associated with bigger number of goals scored. So, this season's Brasileirão is not crushing Pep Guardiola's thesis, but on the contrary, is confirming it.

As a matter of curiosity, let's analyze Corinthians matches. From the 16 winnings so far (round 25), only in 6 of them Corinthians ended the game with more possession than their rivals, that is, only in 37.5% of the times they won they had more possession after the final wistle.

Nevertheless, from the 35 goals scored until now, in 52% of the times, Corinthians had more possession in the game state previous to the goal. That is, in most cases that Corinthians score, they more possession than opposition until that moment. Thus, Corinthians is not a team that wins "handing" possession to rivals, but the opposite, the majority of the goals scored happen in a moment of the game that they have more possession. Although, after scoring, they have less possession and handle to keep without suffering a goal.

Another example. From the 13 wins of Grêmio until round 25, only in 6 of them they ended the game with more possession; that is, 46% of the time. Although, 55% of the 40 goals scored so far, happened when Grêmio had more possession in the game state previous to the goal.

These numbers give a different reading than usual. Football is a dynamic game, so it is important to evaluate some statistics, such as possession of the ball, conditional to the score of the match in each moment of the game. The problem in looking only at the ball possession at the end of the match is that we will observe the net effect of two opposing signal effects: BIG ball possession generates MORE goals (positive effect); and MORE goals yields MINOR ball possession (negative effect). However, we are interested, in most cases, only in the positive effect. Conditioning the possession of the ball on the match board is important, but the analyzes done so far are not taking this into account.

In summary, in this post was defined a fairly clear concept for a ball possession statistics. I have shown that different sites use different definitions of ball possession, and that these definitions have no explanation. I have shown that clubs that win matches usually end the game with less possession of the ball. At first this result suggests that goals scored are associated with less ball possession. However, we must analyze the conditional ball possession of the game state! When we condition the possession of the ball to the game state, we see that the clubs score most of their goals when they have more possession of the ball until the goal scored. Therefore, when analyzing the possession of the ball, we should look at conditional possession of the match board (not just look at the possession of the ball at the end of the match). Corinthians scored most of their goals while having more possession than their opponents. The same thing happened with Grêmio.

Finally, the current brazilian season brings evidence in favor of the thesis of Pep Guardiola; in soccer, wins who has the ball in the feet.