The game has changed

It is quite clear the game has changed a lot. Teams like the current Champions League champion and their predecessor Liverpool simply wouldn’t make any sence before 91, when it was still allowed the kepper to get the balls with their hands after a pass from a teammate. Why will we press high if a simple pass back to the keeper breaks all our strategy?

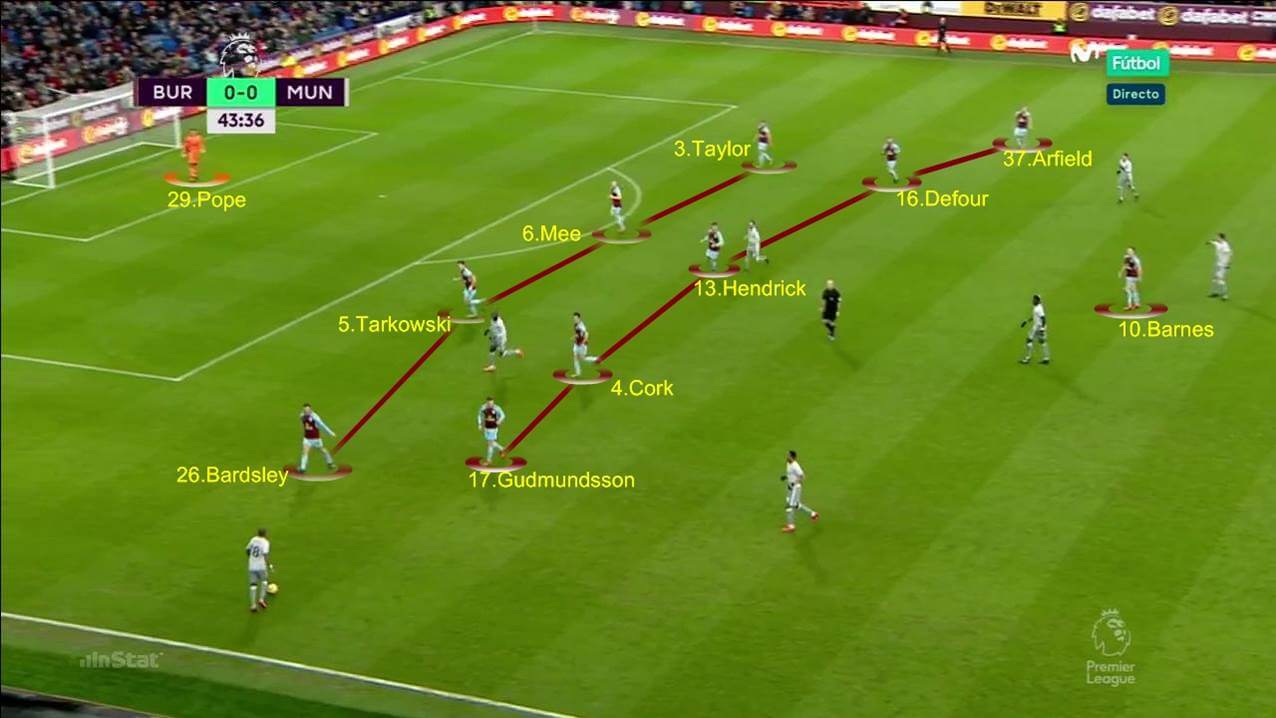

One of the most notable things about the modern footbal is related to the space occupied. It is not rare to see a bunch of players squeezed in a small part of the pitch. And this happens especially in the areas of definition of plays: the team that defend is compacted with the two lines, protecting the central strip of the pitch, while the attacking team is moving the ball from one side to the other, trying to find the space to infiltrate or shoot.

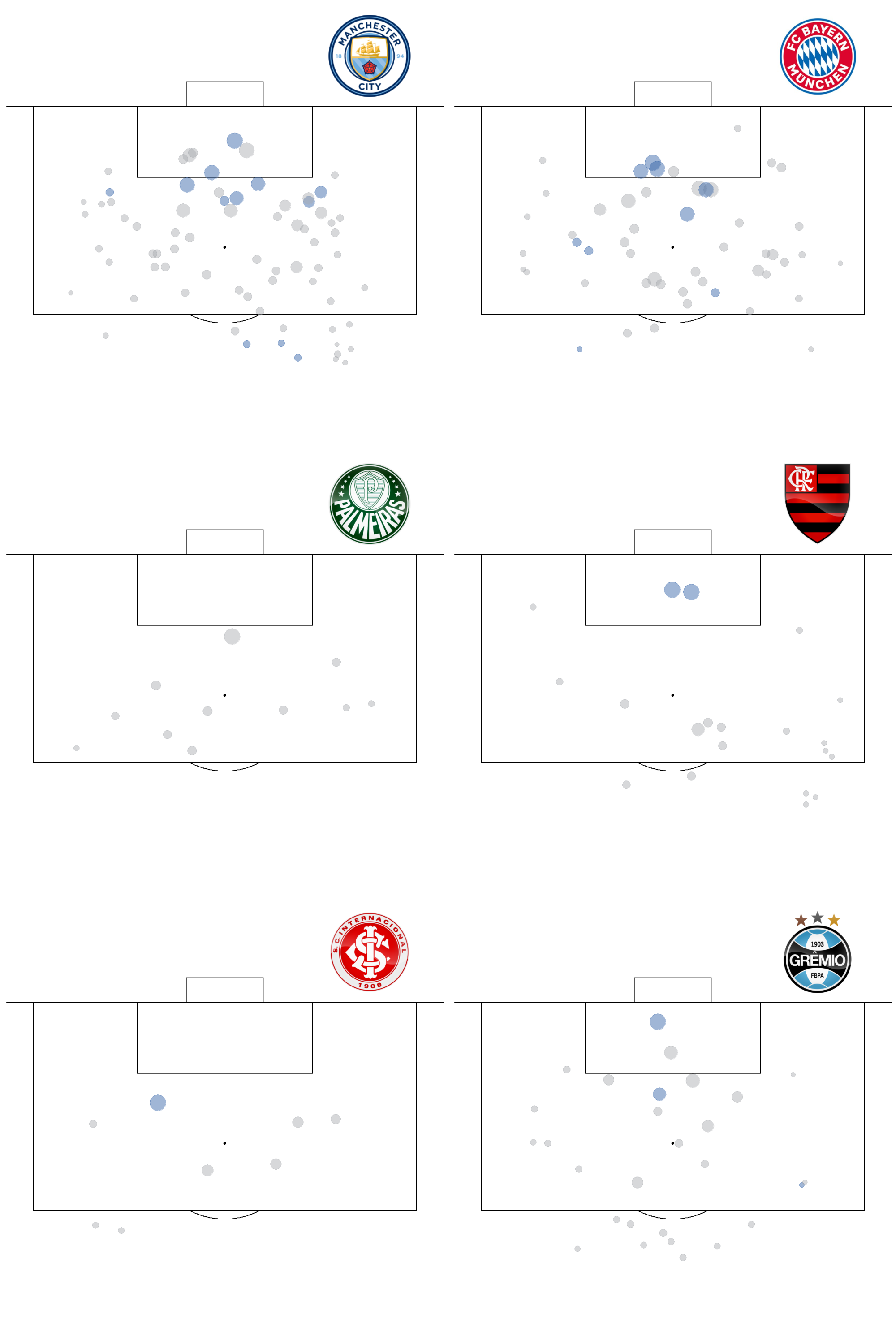

Watching Premier League and Brasileirão matches, something caught my attention. Manchester City is perhaps the greatest representative of Juego de Posicion , a style of play that keeps possession as much as it can, moving up the pitch in a secure and gradual way, which naturally pushes the opponent to their defense pitch, protecting every with space with all or almost all players. Still, they can manage to shoot from positions with high xG. In Brazil, many teams face similar situation, with the opponent parking the bus in front of the goal, but they just can’t reach the same spots for shooting like Manchester City do.

It gets quite clear in the images below. Using data from 2018 for the Brazilian League, 17-18 for Premier League and 19-20 for Bundesliga, it shows all shots with the following filters:

- Plays with at least 10 passes

- Only Regular Play (no counter attacks or set pieces)

- Only foot shots (no headers)

- Plays that had at least one moment in the defensive side

Thus we increase the chance of filtering plays that the defense had their lines low. Note: Bayern Munich had only 34 matches, while the others 38.

¹Blue points are the goals.

Ok, maybe the comparsion is a bit unfair, after all we are talking about the english champion with the most points in history, and the european champion Bayern Munich, one of the most incredible sides I’ve seen, with the 4 top teams of Brasileirão 2018, which in my opinion, was one of the poorest seasons I’ve ever seen. But we could replicate it for other leagues and seasons, and the pattern would come again - braziliam teams, with very few exceptions (Flamengo 2019, for example), have lots of difficulties in creating opportunities where the xG is high (or we could say, areas closer to the goal).

Expected Goals don’t tell everything

Speaking of xG, we need to revisit this metric, beucase even though it is one of the best tools we have to analyze the teams, it misses many things yet. Expected goals is a statistical model that attributes the probability of a shot becoming a goal, considering some variables. Those variables change depending on whom made the model, but some things are basic: the distance of where the shot took place to the goal, the angle generated, if the shot was by foot or head, the type of the play - regular play, counter attack, corner, etc. Still, the most important ones are the distance and angle. The previous images showed this - the size of the points depend on the xG - the bigger the point, the greater the xG, and it gets quite clear that it goes smaller when it gets further from the goal. What xG does not tell us is the context in which that shot was taken place, and that makes the whole difference.

Pressure and blockings

Since its initial conception, xG has gone through some changes in order to try to describe better which variables impact the most a goal opportunity. The most relevant ones are from StatsBomb . They included the height of the ball and also the pressure made by opponents. These are variables that anyone that once played football, knows the impact it has on the quality of the shot to come. Still, analyzing data that Statsbomb provides freely, we see that their definition is quite ample, specially in relation to the position of the defensor: he or she can be in front of the attacker or even coming from behind. Pressure seems to me to be function of the speed that the defensor reaches the attackers, rather than its position.

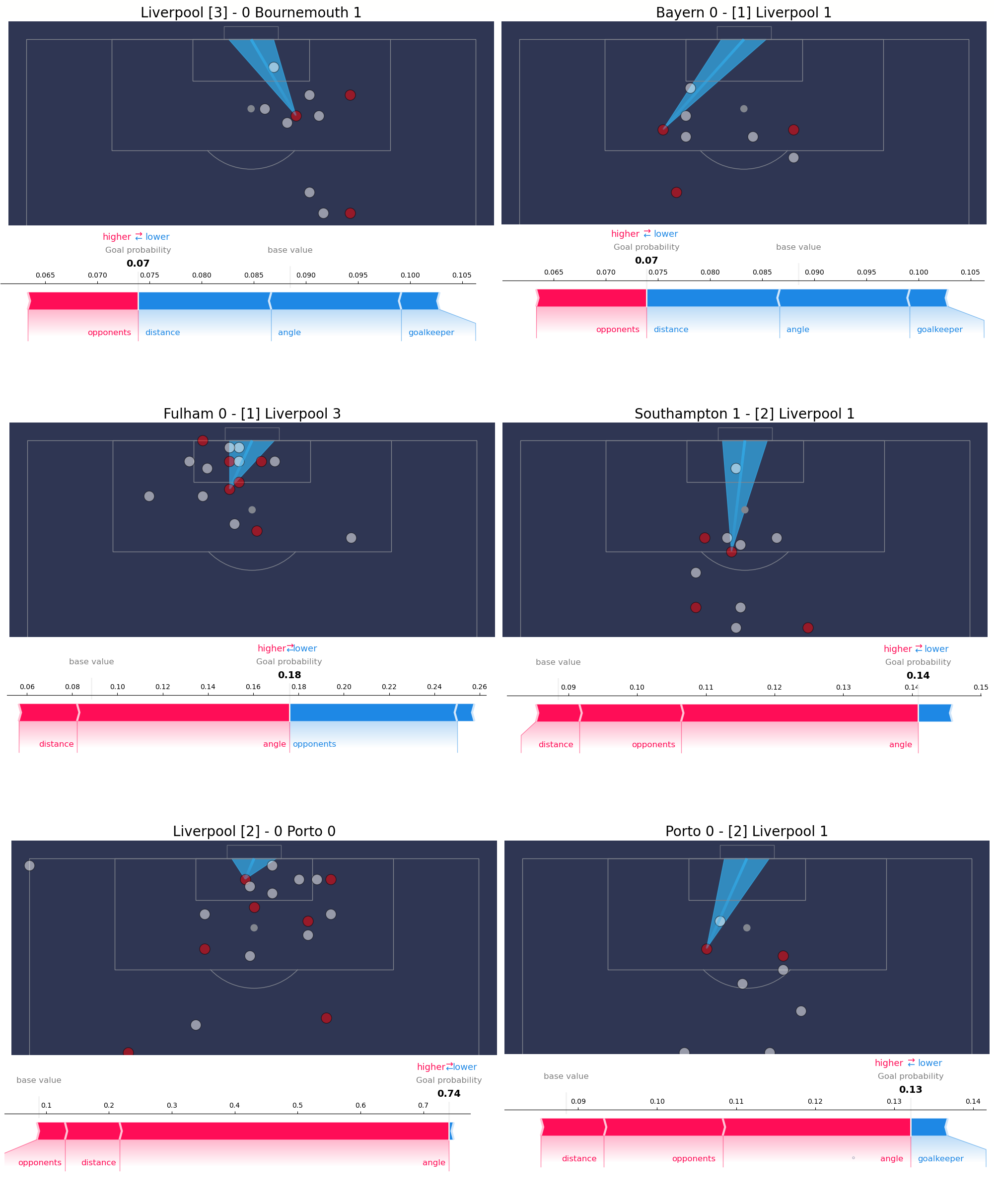

The most recent xG model I saw, which brings some extremelly relevent information to describe the quality of a goal scoring opportunity, is on the post by @jernejfl (https://twitter.com/jernejfl), where he takes into account also the quantity of opponents in front of the attacking players, blocking the shot.

Imagens by @jernejfl

The red and blue bars indicate the contribution (positive or negative) of the variable related to score a goal. In Liverpool’s goal against Fulham, the blue bar, which corresponds to the opponents, is quite large, showing that the fact of having defensors blocking the path to the goal, decreases considerably the chance of a goal.

The path between the attacking player and the goal is central in this study, and that’s what we’re going to explore now.

How to score a goal?

That’s the million dollar question (actually, judging by the spends of teams, it must be much more than that). A goal is something extremelly complex, and I don’t have the least pretention to create outrageous theories or bring senseless statistics to explain the ball in the back of the net. There’s the influence of so many things that can lead to a goal, from ball events such as a dribling that generates space for the shot, as events without the ball - the moves of a striker, that takes the defensor with him, that opens up the space… Well, it is just hard to explain chaos and its unfolding. But some things are basic in terms of goal scoring. Let’s begin by the simplest of all: the trajectory of the ball.

Being the most straightforward possible: For a goal to occur, the trajectory of the ball, between the attacking players and the goal, must be free, without blockings that might prevent the ball from going to its initial point - the foot (or the head) of the player, and the back of the net. There’s absolutley nothing genious about this (although some players defy phisics by shooting on the defender), but it will make sense in a bit. Reviewing the first part of the text, the game today offers much less space than other times, and that makes harder for the players to find that space between them and the goal, for a shot to take the risk of becoming a goal. It is not few times that in the Brasileirao we see the attacking side moving and moving the ball, so in the end they just cross it.

What are the chances of scoring a goal by crossing when they have 9 players in the big box?

Now that we know the basic condition for a goal to happen, we can go to the next step and try to understand how this space is generated, and which context. One way would be hiring players like Ronaldinho, that sometimes do wizard tricks and find space where we thought there was none. Unfortunatelly, he is only one and has retired a while ago, so we will have to look for other ways to find that space.

Is Ronaldinho in your team? So keep reading the text.

How to generate that space?

Sometime ago, a remarkable man spoke about space and time, that the two things were deeply connected. That guy was simply Xavi Hernández. And what Xavi said many times, is the main point I’m tying to make on this text. Space and time have fundamental relation in footbal, especially in goal scoring.

A small review of what we have seen so far: we know that we need the path of the shoot and the goal free, and we also know that defenses have conceded less and less space. Now, we need to look at time, because that’s what will give us the space we need to shoot to the goal.

In the plays we spoke about, at the begining of the text, defenses are in low blocks, very compact, and the attacking team moves the ball from onde side to another. There, space and time relate in an inverse way: the longer I have the ball, less space I have to do what I want; the less time I keep it, more space. That implies that, for me to have a shot with greater chances of scoring a goal, I have to have the ball the least amount of time possible. That means: shots on the sight.

The theory

Teams like Manchester City and Bayern Munich keep the possession, push their opponents to their defensive side, but still manage to find spaces so they can shoot with high probability of scoring a goal, and that happens because, when they shoot, the players that do so don’t keep the ball; they do not control the ball and think what to do, they shoot on the sight.

Have you ever seen City score a goal like that?

Assistance and shot fast enough to take the free space in that short interval.

You may think that, in the examples above, Foden and Müller only had the option to shoot. Yes, that can be truth, but that is the main difference for brazilian football. These top teams know they won’t have space, and depending on dribbling to break lines or simply cross the ball so the striker can head it, shortens a lot the possibilities of goal scoring; top teams do those plays in which the shot is on the sight by design!

The traditional cut backs plays of Manchester City and Arsenal are classical examples. The play is prepared so the striker gets to the ball shooting with only one touch, this way he does not have the pressure or resistance of defenders, therefore more space and angle for the goal.

The real threat is related to the space the shooter has free in front of him.

Just a reminder: we look for the space for the shot, and the time of possession generates that space - it is not the cause for the shot. That gets clear when we analyze fastbreak plays, that may have a longer possession. It happens because, in fastbreaks, sometimes the players moves through the pitch with no or few opponents, due to the space occupation of the other team.

Bale keeps the ball for around 7s. We are looking for the space to shoot!

What data say

It is not possible to do this analysis with the data we usually use. That is because most of the data suppliers do not get the data regarding time accurately, and 1s makes all difference in this case. That was only possible with data provided by StatsBomb, that I made sure could fit for this study (yes, I watched tons of plays and checked the time of it). StatsBomb provides around 800 matches freely (check https://statsbomb.com/academy/) - for this analysis, we used only La Liga data, from many seasons. Now, lets go to data.

There are 7177 shots in the 485 matches of our sample. With the filters we want, which are:

Only shots by foot

Only Regular Play

At least 10 passes in the play

The shot is after a pass of a teammate (no rebounds)

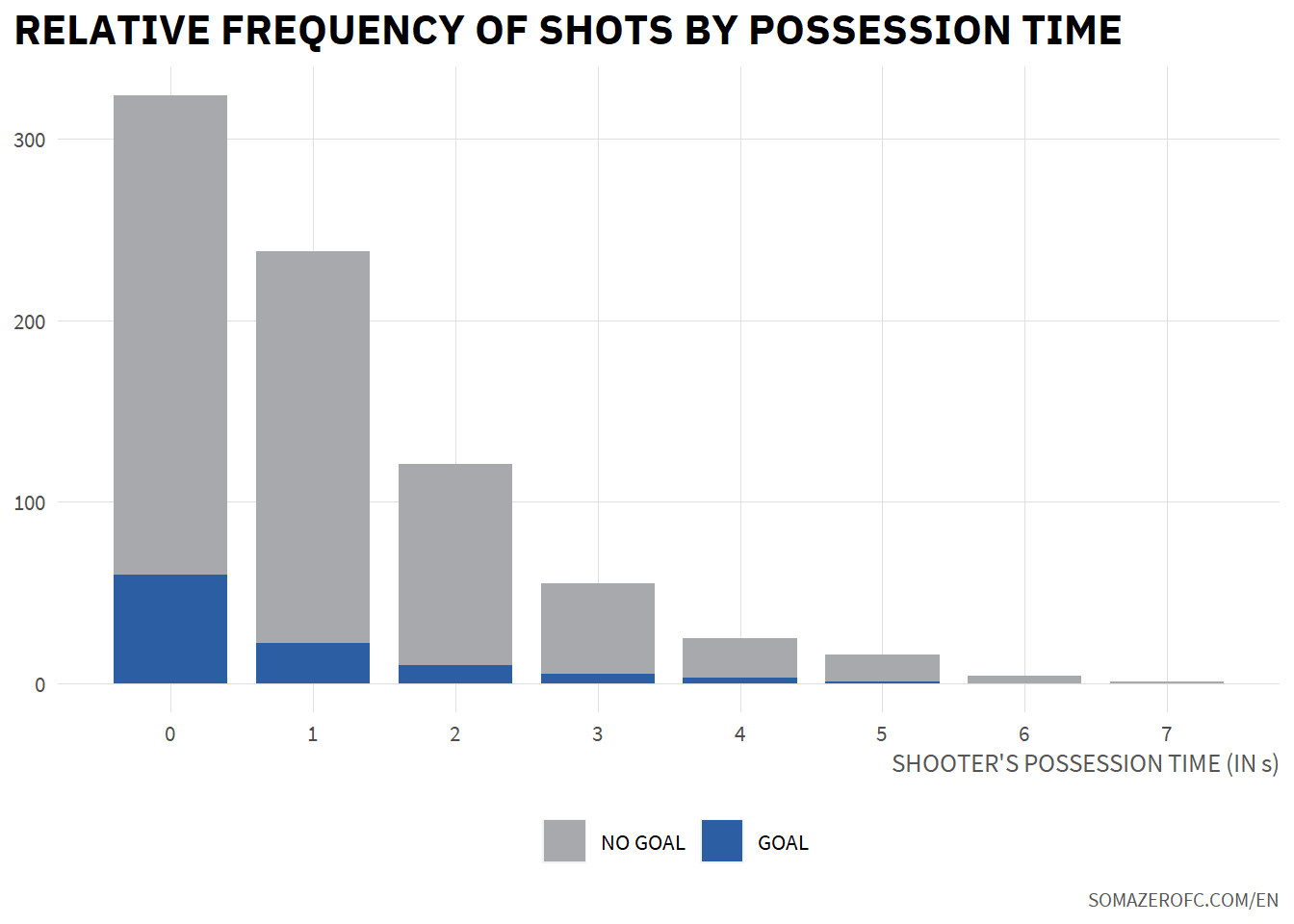

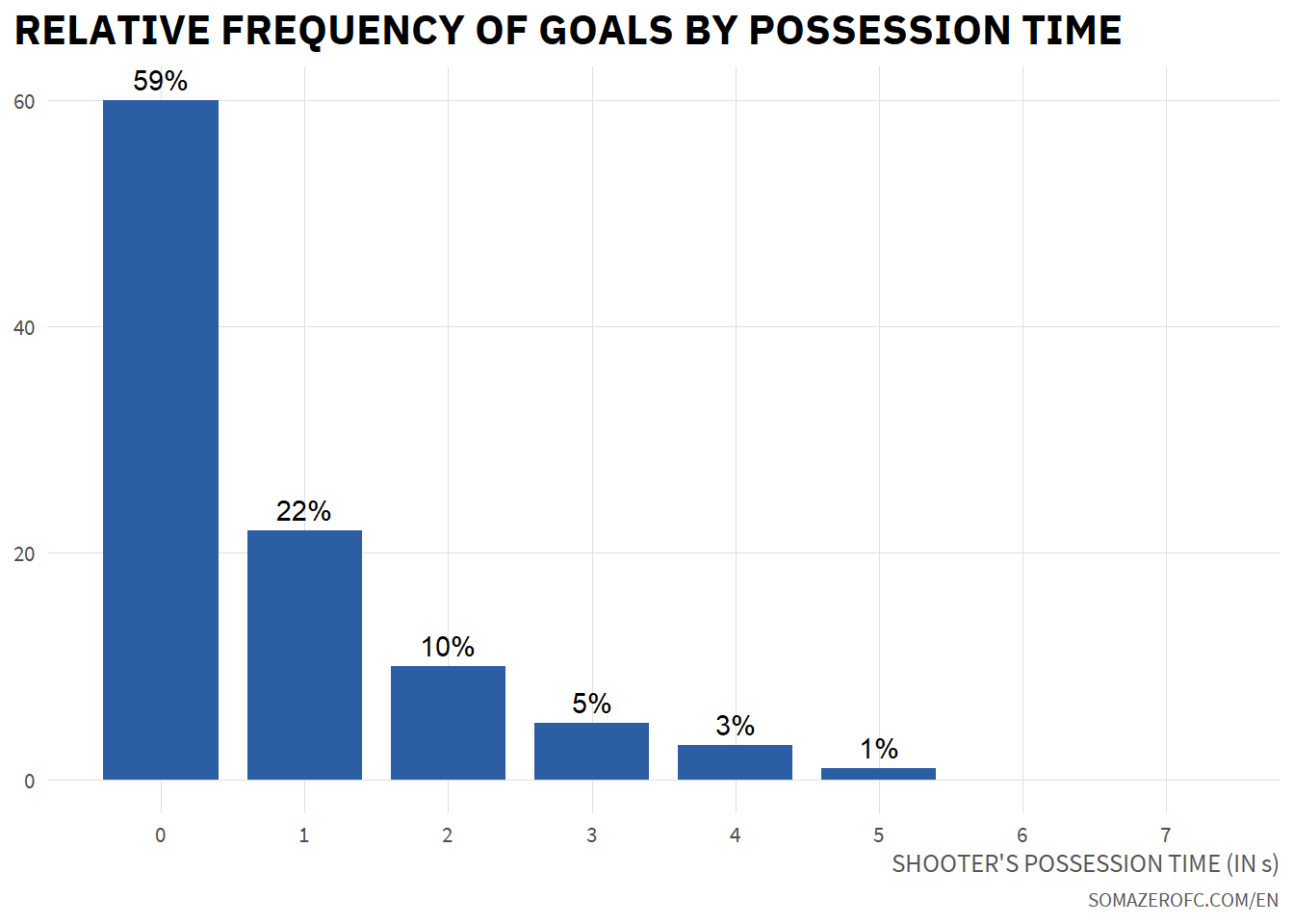

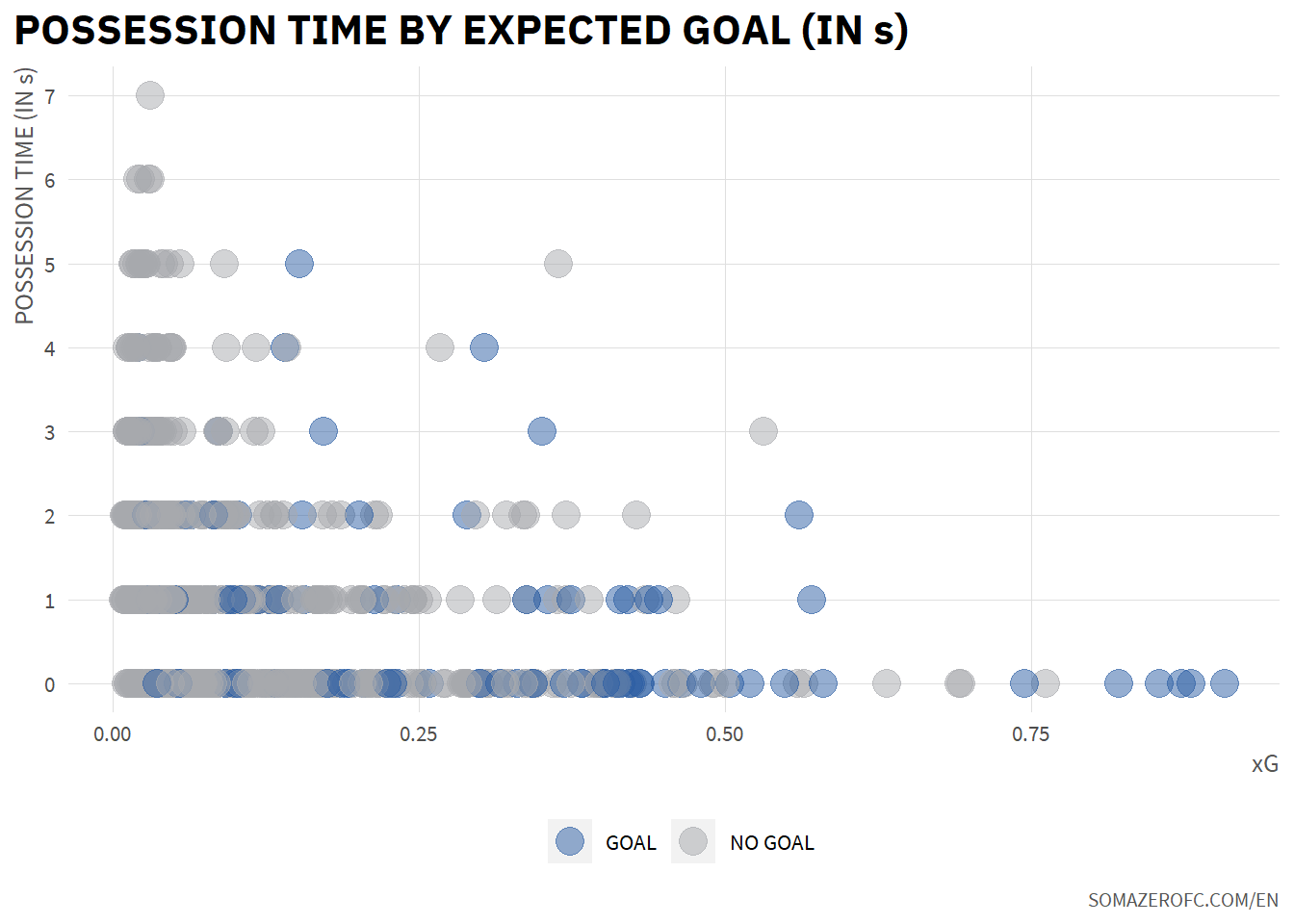

we end up with 784 shots. Most of them take place with 0s of possession time, around 41% of the sample. But also, shots on the sight have the biggest percentage of goals, 19%, while longer possessions shortens a lot these numbers. Below, the relative frequency of only goals.

The plot above is quite clear about goals and shots on the sight. If we consider up to 1s of possession time, we are talking about 80% of goals. Let’s move to the next plots, which for me, are the most interesting ones. We will relate possession time of the player who shoots and the xG of his shot.

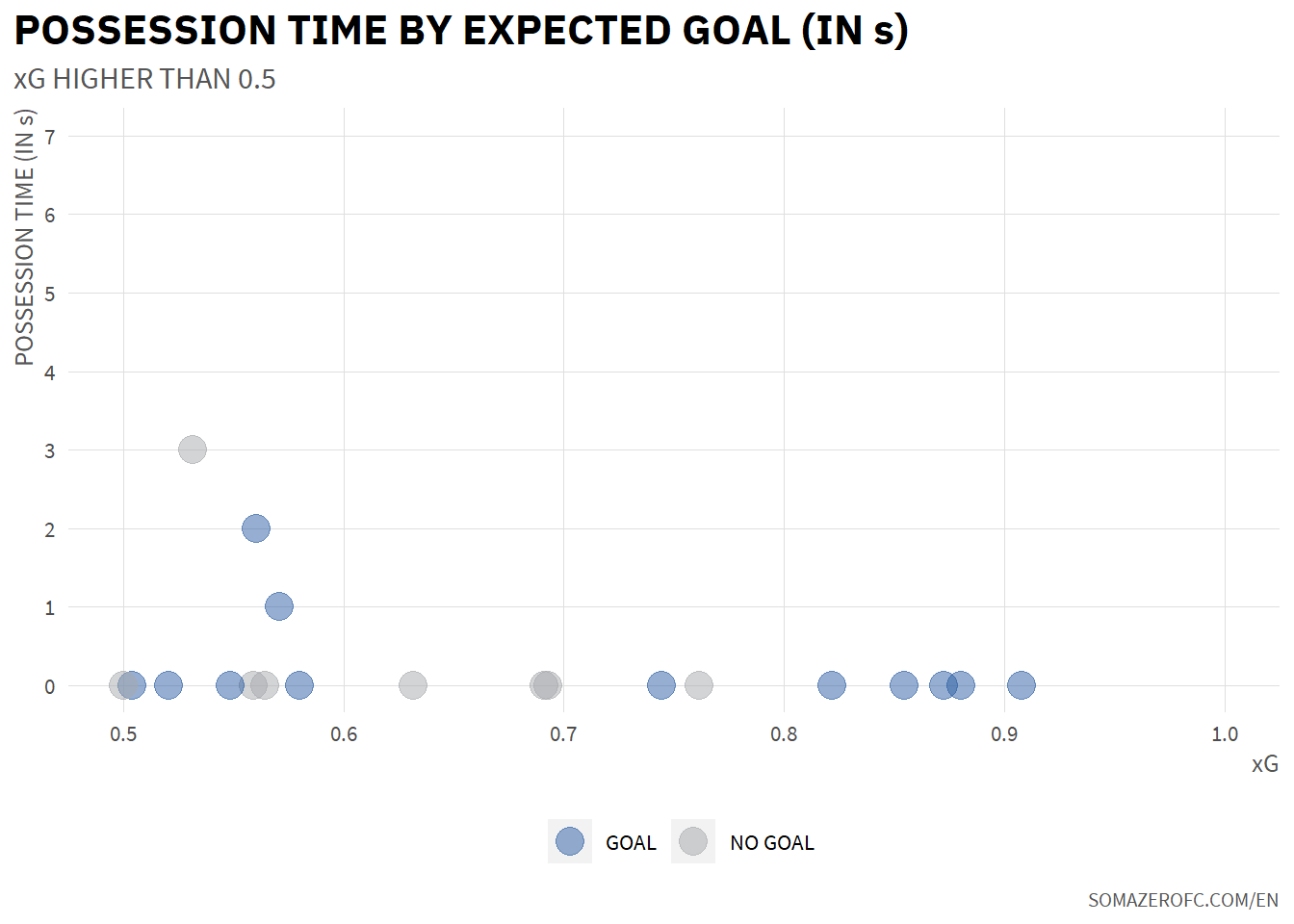

One touch finishes take place in many areas of the pitch, from the less likely (lower xG) to the most likely (higher xG) of being goal; but the interesting thing about the plot is its triangle shape, which means: to have access to the most probable regions of the pitch to score a goal, it has to be really fast. If we cut the plot, showing only shots with xG higher than 0.5, it will show us that the majority of shots were one touch.

It is quite clear that shots in regions with higher possibilities of goal scoring happen only with possession time close to 0.

Implications

Ok, so possession time is key to have space for shots with higher chances of goals, but it does not mean that if I simply shoot from anywhere, as long as it is a shot on the sight, I will increase my chances of goal. We need to understand how these plays are generated, so that the player can shoot in one touch. We spoke briefly about the cut back plays of Arsenal and Manchester City, that are examples of plays that induce the shot in one touch. But obviously they are not the only type of play for that. City and Liverpool build up to the goal in different manners, but still, most of their regular play goals (empirically, as I said before, with the data we work, we can’t do this analysis) fall into the same principle of possession time in shots.

Watching Brasileirão and european leagues, the impression I have is that, though these kind of plays do take place, they are not intended. If it is not a cross, most of one touch shots happen by chance, like in a rebound. That is because we still have individual skills as root for our solutions - the talent of the players, that has given us so much happines, will solve this problem. This is a great bias. We have in our minds the genious plays of great players from the past, that would dribble 2 or 3 players and score a golazo. But what we don’t take into account is the tons of times that players tried to dribble and lost the ball, when a simple one-two play would have been much more efficient. I’m not saying I’m against dribbling, obviously not, but it has to be used in the right time, in the right place. Dribblings are overrated to generated those spaces. Colective plays, such as one-two, are much easier to be done and can have very good results in this aspect.

In terms of strategy, we need to focus in how to create those situations. What is the ideal positioning in the last third, in a way that a combination of passes generates more space so my striker can shoot in one touch? Which situations my winger should try to dribble and which he should seek a teammate for a one-two? Or how can we avoid the other team to generate cut backs?

Next steps

The first thing is to verify the data regarding other leagues, if there is big difference among them. So far, we depend on companies that use StatsBomb data; or the other suppliers could increase accuracy of time events.

Tracking data would be great to evaluate the position of players in the analyzed plays. They would help a lot with, for instance, what is the optimal move and which spaces to attack.

This text is only the begining of everything we could explore in this subject. Since it’s poped up in my mind, every match I’ve watched I was paying attention in possession time, space and patterns of play. It’s been more than an year, and what I could perceive is teams that induce plays that end up in shots in one touch end up being much more dangerous in their attacks, which is a great advantage.

It also would be interesting to understand the relation between space and time not only for shots, but the passes that precede the shots. Finally, the subject is huge and full of possibilities, and I don’t intend to write only this one piece of text, so, as possible, I’m bringing new ideas over it.